Adversarial Machine Learning

An Overview

I’m sure you’ve heard about convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and how they’re able to detect images at near human-like accuracy. However, this isn’t always the case. It’s possible to trick these CNNs, and any other machine learning model for that matter. It turns out it’s currently not even that hard. This is the field of adversarial machine learning.

Quick Intro to ML

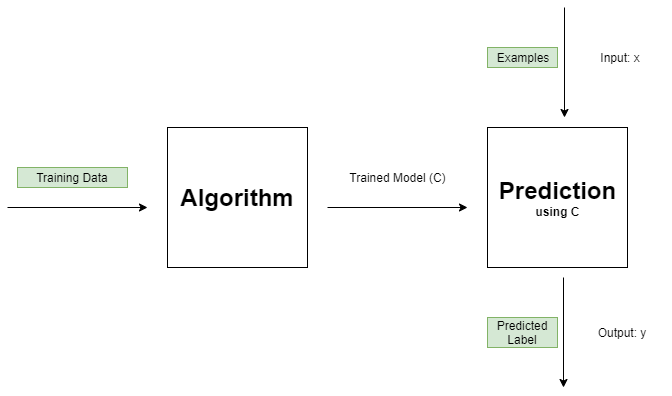

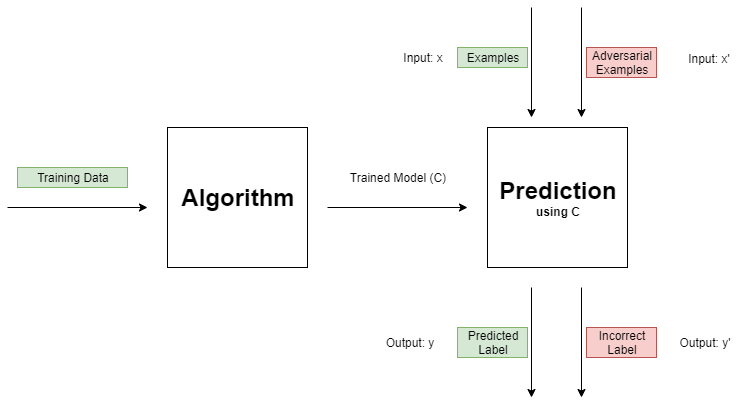

Here we will mostly think of machine learning in a general sense instead of digging too deeply into what is actually happening. So, here is a quick diagram that shows the basic idea of a machine learning model.

Some algorithm takes (usually) mass amounts of training data (consisting of a set of data points and their corresponding label) and it outputs a trained model C, such as a neural network or a random forest. We can now query this model with some input data x and receive a label y in return. This is a very basic overview of classification using machine learning. (Regression is quite similar, the main difference is the output values are continuous for regression while they are discrete for classification.)

(It’s worth noting that this is an example of supervised learning as the training data consists of data points AND their labels.)

Overview

Now, there’s two main ways to attack machine learning models. They are both through data as that is its connection to the “outside world.” The training data going into the model can be attacked or the test data going into the model can be attacked. The former is known as data poisoning while the latter is known as an adversarial example. I’ll give a brief overview of each and then go into a bit more detail later.

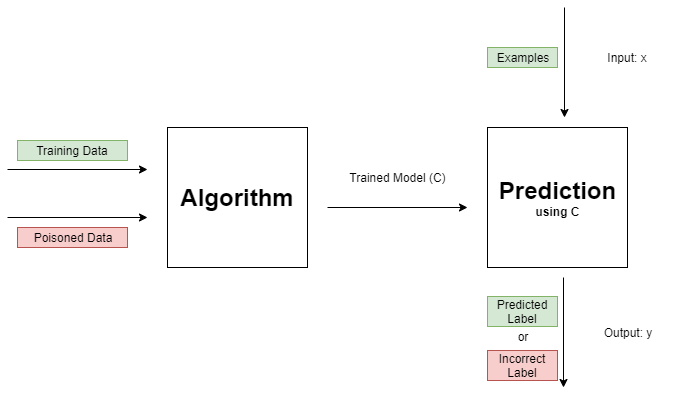

Data Poisoning Overview

Usually people don’t worry about the training set; they assume it’s fine. In a data poisoning attack, however, an attacker is able to modify the training set. This is usually thought of as the attacker adding bad data points as opposed to modifying existing ones. It will generally be much easier for an attacker to do this, as they could do something like create a new account with bad data (on IMDb, Netflix, etc) or upload bad articles or images to the Internet and wait for a scrapper to pick them up. Modifying data would often look something like editing entries in a secure database or an existing user account, which is very difficult if not impossible.

Adversarial Example Overview

As for adversarial examples, they are test images that have been slightly modified (often in a way that is imperceptible to the human eye) in such a way as to fool classifiers. This takes a different form when the classifier gathers images from cameras, as in a self-driving vehicle.

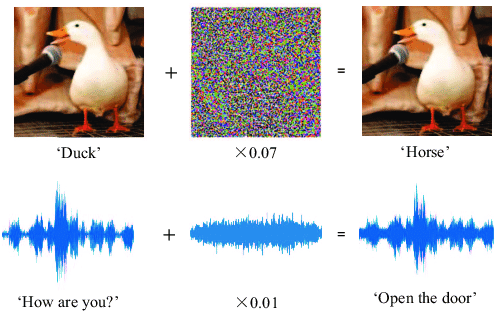

These two examples will really highlight the problems and dangers that adversarial examples can cause.

The duck example highlights what I said earlier: adversarial examples can be completely imperceptible to humans. I wouldn’t recommend staring at those images long enough to see a difference, but feel free to try.

The second example shows that image classifiers aren’t the only classifiers that are vulnerable, audio classifiers are as well. While we can’t hear the changes to the audio, the structure does look quite similar after the noise is added.

(The following website has good examples of original and modified audio files: https://nicholas.carlini.com/code/audio_adversarial_examples )

Now, this is an example of how something like a self-driving car can be attacked. Since the car manually takes pictures, a different approach is needed to fooling the classifier as we don’t have access to the images that the cameras take. So the stop sign has been physically modified. This and other adversarial attacks against signs can seem like common graffiti to people that aren’t aware of what these modifications can do. The severity of traffic sign misclassification is also important to note. If a self-driving car misclassifies a stop sign as a speed limit sign, that’s a very dangerous misclassification. So, we clearly need to be worried about adversarial examples.

Targeted vs Untargeted

There are two types of attacks: targeted and untargeted. They will both be discussed for data poisoning and for adversarial examples in their respective sections.

Data Poisoning

When I briefly talked about data poisoning before, your first thought might have been, “Well, why don’t we try to eliminate these bad data points before training our model?” While that is a very good point, it turns out that this is very difficult if we don’t know the true distribution of the classes. However, since we are now dealing with a training set that already includes poisoned data, the distribution that we have includes both the good and the poisoned data. This makes it hard to remove the outliers by using the true distribution of their respective class as the distribution itself could have been significantly shifted by the poisoned data.

Anyway, the general technique of trying to remove data poisoned points is called data sanitization while removing outliers is just one way of executing this. One quick example of how to do this would be to find the center for each class and then to remove those data points that are furthest away from the center/ further than some threshold. A problem with this loops back up to what I mentioned earlier - that we don’t necessarily know the true distribution for each class because our data is already poisoned.

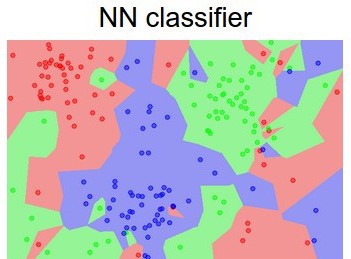

Now, onto our discussion of untargeted and targeted attacks. Untargeted attacks would be something like bad data being added to degrade the model’s accuracy. They would be shifting the decision boundaries for most or all of the classes. Since we’re typically dealing with tens of dimensions, hundreds of dimensions, or even more, a lot of data points tend to fall near these boundaries. (An easy way to think about decision boundaries is with the following image )

In this image, there’s only two dimensions, the x and y axes. Already many data points are close to a border. As the data has more and more dimensions, more and more data points will be near some border. So shifting many of these decision boundaries even slightly can lead to points being misclassified.

On the other hand, targeted attacks have a more concrete goal in mind. They are trying to get some image or set of images misclassified as some target label. So, they want to shift the decision boundary for one class. If they are able to find some image(s) (and by find, I really mean compute) that are close to the target image, then they can feed those poisoned images to the model with the target label during training. The model will likely shift its decision boundary for the target class enough to include those poisoned images. Since they were close to the target image, it will likely also be classified as the target class.

Adversarial Examples

We can think of a neural network as a function C (the trained model in the diagram) that maps an input x to a class y. We can think of an attacker as a function A that maps some x to x’. The attacker can only modify each element of x by so much (usually denoted by 𝝐, epsilon). So, the attacker’s goal is to modify x in such a way that C maps x’ to some incorrect class.

There are many ways to do this, such as the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), however some of these attacks, such as FGSM, have been shown to be not that effective when there is some sort of defense in place. Still, the four general categories of attacks are gradient-based attacks, score-based attacks, transfer-based attacks, and decision-based attacks.

-

Gradient-based attacks have access to the entire model and all of its inner workings (so it is white box). They use the gradients produced in the back-propagation phase of neural network training to quickly find effective adversarial examples. Examples of this kind of attack include FGSM and DeepFool.

-

Score-based attacks are similar to gradient-based attacks, but they only have access to the probabilities (the scores) output by the model. Through this, they are able to estimate the gradients.

-

Transfer-based attacks rely on the fact that adversarial examples for one network transfer to another network (given they’re trying to classify the same sort of things). So, we could find adversarial examples (using some other method) for a similar network to the one we’re trying to attack. That adversarial example, given it fools our new network, should also fool the network that we are attacking. In this way it doesn’t matter how much or little we know about the network we’re attacking. As long as we know what labels it gives then we should be able to find adversarial examples for it.

-

Decision-based attacks assumes a black box setting, that is, it knows nothing about the model. It can only give the model an image (or some other form of data) and view its output decision. This form of attack is the most practical as in most real-life instances, an attacker will only be able to query the model they are trying to attack.

Now, you may be thinking: “Well, why don’t we just focus on trying to detect these adversarial examples?” While that is a good point, it has actually been shown that most known detection methods can be fooled with sufficiently strong attacks. (Carlini & Wagner 2017, 1st reference)

One other possible solution is a new family of networks that are naturally robust to adversarial attacks. However, I don’t know that any progress has been made on this front.

Now, for adversarial examples, untargeted attacks are simply meant to get the image to be misclassified as any label. Perturbations to an image (changes to the values of its pixels) are less restricted as the only goal is to change the label. Targeted attacks are trying to misclassify the image as some target class y’. Here, perturbations are a bit restricted as the goal is to change the image from having label y to some target label y’.

A Notebook

I wrote a notebook that uses a library called Foolbox to construct adversarial examples for an Inception-V3 model. You just need to pick the number of adversarial examples to find (1-20 range), run the whole notebook, and then scroll down to see various data it computed as it was going and then the final graphs.

Note: It uses a handful of libraries, notably PyTorch and Foolbox. They are all imported at the top of the notebook, so you can see which you need. The above kernel will install Foolbox in the second cell.

Note: I also have an additional notebook on GitHub that includes an option to get adversarial examples for an MNIST model. There is a CNN for MNIST in that folder as well. If you would like to use the notebook yourself and want to generate adversarial images for MNIST, be sure to grab that as well!

Conclusion

There are two ways to attack a machine learning model: data poisoning and adversarial examples. Data poisoning occurs in the training phase while adversarial examples occur in the testing phase. Both can deteriorate the model’s quality. Adversarial examples are especially dangerous because of the impact they can currently have on dangerous tasks like self-driving cars.

This has been a mostly high-level overview of adversarial machine learning. I hope you’ve enjoyed! References and some suggested readings can be found below.

Some Suggested Readings / References

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1608.04644.pdf - fantastic paper that nicely describes a lot of things without going as in-depth as most papers do (especially the background section)

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1707.08945.pdf - talks about physical adversarial examples (traffic signs)

-

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.04248.pdf - the introduction to this paper gives a very nice overview of the different categories of adversarial attacks (overall it is a paper about decision-based attacks, which I plan to cover more in-depth later)